Categories

Change Password!

Reset Password!

Fever is a physiologically controlled temperature increase with a strong upper limit, regulated by protective endogenous antipyretics and thermosensitive neuron inactivity at temperatures above 42˚C. It’s a common health concern, rarely reaches 41˚C and is not as dangerous as feared by parents and health professionals.

Parents and carers should identify danger symptoms and assess conditions beyond fever, prioritize social and physical environment enhancement over fever reduction, and use antipyretic medicine as first-line treatment for healthy children with acute febrile illness.

Fever is a physiologically controlled temperature increase with a strong upper limit, regulated by protective endogenous antipyretics and thermosensitive neuron inactivity at temperatures above 42˚C. It’s a common health concern, rarely reaches 41˚C and is not as dangerous as feared by parents and health professionals. The growth of "fever-phobia" is attributed to worries held by parents, tutors, and caregivers about potentially dangerous causes of fever, such as severe bacterial infections, and false beliefs that fever is a sufficient trigger for brain damage.

Numerous research studies have reported a significant proportion of parents, instructors, and caregivers administering antipyretics when there is little to no fever with incorrect dosage, or inadequate time between doses. Fever is a physiological response that helps fight illness and has no long-term negative consequences on the nervous system. Relieving the child's suffering rather than lowering their body temperature should be the main objective of treating fever in children.

Improper fever control can impede diagnosis and raise the possibility of overdosing on antipyretics. Additionally, using rectal formulations, administering these medications in the presence of underlying illnesses for which they are contraindicated, and switching between or combining the use of two antipyretics are other variables may exacerbate drug toxicity. Lastly, excessive therapy could have a big financial effect in high- and low-income nations.

The diverse attitudes towards fever have resulted in inconsistencies in managing it. Despite evidence suggesting fever as an evolutionary resource aiding in overcoming acute infections, many healthcare providers and parents view it as a dangerous condition. In the USA, an accidental overdose of paracetamol resulted in 100 fatalities in 2006. Since antipyretic medication can be detrimental, organizations have produced clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) to manage fever in children.

CPGs guide treatment, eliminate evidence-based disparities, and lessen irrational fear and excessive suppression attempts. A review of seven CPGs found that even high-quality guidelines are not comprehensive or consistent in their recommendations. The entire range of recommendations for treating childhood fever is still unknown. Therefore, it is necessary to summarize all recommendations and assess the evidence level for each recommendation offered by the CPGs currently in use for fever treatment.

RATIONALE BEHIND RESEARCH

Even with the most recent recommendations, there is no consensus advice that is supported by the data, and many of them contradict it. The threshold question remains unanswered despite its basic relevance. Guidelines remain problematic for the most common intervention (antipyresis). So far, no comprehensive evaluation of the evidence supporting the CPG recommendations for fever has been conducted.

OBJECTIVE

To perform a comprehensive evidence-based assessment of CPGs for the symptomatic management of pediatric fever.

Literature search

The study used various databases viz., PubMed, Google Scholar, pediatric society websites and guideline databases to locate CPGs (documents on symptomatic fever management in children, issued by governmental organizations, pediatric associations, or other healthcare groups) from each of the 195 countries, covering the period from 1995 to 2020. The International Pediatric Association's website was used to scrutinize relevant documents related to fever among national pediatric associations.

The Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, or OCEBM, evaluated the quality of the evidence pertaining to each recommendation. To examine the body of evidence pertaining to the threshold for starting antipyresis, a GRADE evaluation was carried out. The systematic review adhered to the PRISMA statement to structure all methods. Suitable medical guideline databases were found via a Google search for "medical guideline databases" and then searched using specific terms.

Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

Articles that were identical to other guidelines or the ones that did not focus on symptomatic management of fever were excluded.

Study selection and data extraction

One reviewer extracted data from all sources into an excel table.

Data and statistical analysis

N/A

Risk of bias and quality assessment

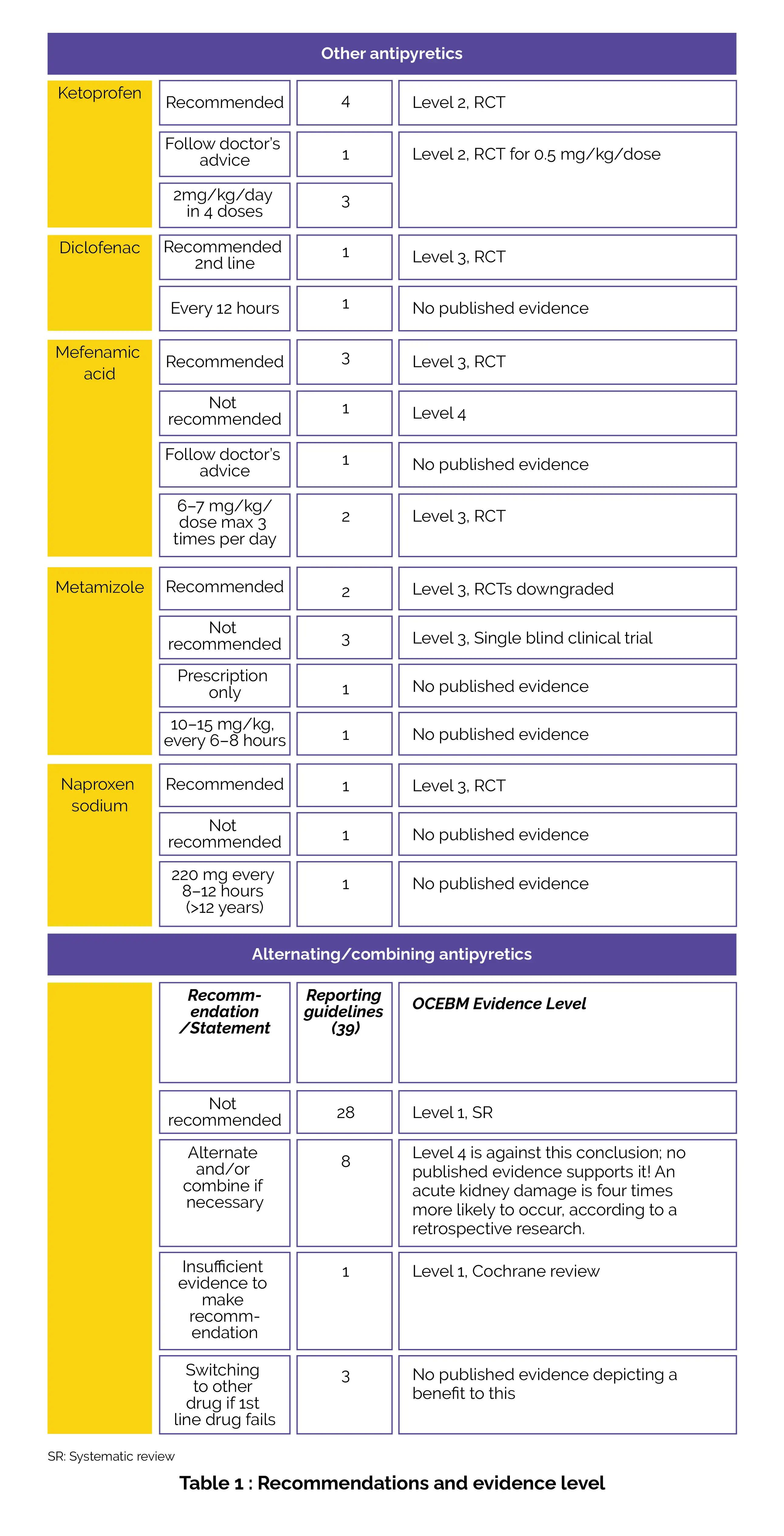

Two investigators analyzed the highest level of supporting evidence using a modified version of the OCEBM Criteria for each recommendation. The best quality evidence was produced by systematic reviews of randomized trials (level 1). This was followed by systematic reviews of observational and single randomized control trials (level 2), individual prospective observational studies, systematic reviews of case reports, and individual case reports (level 3), individual case reports (level 4), and mechanistic explanations (level 5).

The OCEBM was modified to assign systematic reviews of prospective observational studies to level 2, case reports to level 3, and suitable non-human studies to level 5. The rigor of systematic reviews was assessed using AMSTAR criteria, with a rating of one level lowered if the review met fewer than 7 out of 11 criteria. For instance, a systematic review of randomized trials was classified as level 2 instead of level 1. Two researchers independently assessed the evidence quality. They resolved any kind of disagreements via discussion.

Study outcomes

N/A

Outcomes

Study and participant characteristics:

Study quality:

N/A

Effect of intervention on the outcome:

Since CPGs present low evidence levels for recommendations and a very low threshold for antipyresis, they need to be improved in terms of methodology, applicability and editorial independence. Thus, it becomes imperative to summarize and evaluate the existing information to produce a consensual and evidence-based fever guideline.

Antipyresis Temperature Threshold: Evidence vs Clinical Practice

Pharmacologic Treatment: Medication Selection, Dosage, Side Effects

Preventing Febrile Seizures with Antipyretics:

Nonpharmacologic Interventions: Bathing, Compressing, Rubbing, and Consuming Fluids

Complementary Recommendations:

Other Potential Issues Not Yet Incorporated In the Issued Guidelines:

Parents and carers should learn to identify danger symptoms and assess conditions beyond fever. Prioritizing social and physical environment enhancement over fever reduction and antipyretic medicine should be the first line of treatment for a healthy child with acute febrile illness. Antipyretics should only be administered if agitated and not mixed or alternated. Increased pain and metabolic strain may result from external cooling.

PLOS One

Symptomatic fever management in children: A systematic review of national and international guidelines

Cari Green et al.

Comments (0)