Categories

Change Password!

Reset Password!

Migraine is a common primary headache condition that impacts nearly 15% of the population.

Scalp acupuncture seems to outperform alternative migraine treatments in terms of effectiveness. But, its safety remains unclear.

Migraine is a common primary headache condition that impacts nearly 15% of the population.

This neurological condition is defined by recurring instances of intense headaches and is frequently accompanied by various other symptoms like sensitivity to light and sound, as well as feelings of vomiting and nausea. Although its precise cause is not completely comprehended, it is presumed to be the outcome of a multifaceted interaction between environmental, lifestyle, and genetic factors. There are 2 types of migraines: those without an aura and those with an aura.

An aura involves temporary visual disturbances like temporary loss of vision, flashing lights, or zigzag lines that precede the headache, and it serves as a predictor of migraine attacks in about 30% of patients. In the 2017 Global Disease Burden (GBD) survey, it was revealed that approximately 1.25 billion people were afflicted by migraines, ranking it as the fifth most widespread condition globally and the seventh most incapacitating illness worldwide. According to the 2019 GBD study, migraine ranks as the second most prevalent cause of disability among young females.

The World Health Organization (WHO) states that the prevalence of migraine is on par with conditions like dementia, quadriplegia, and mental illness, highlighting its status as one of the most severe, enduring, and debilitating illnesses worldwide. Migraines can have a profound negative impact on a person's quality of life, causing severe pain and impeding their everyday activities. Hence, it is imperative to discover useful therapeutic options for migraine in order to enhance the quality of life for those dealing with this illness.

The typical approach to treating migraines encompasses a combination of lifestyle adjustments, like evading triggers, enhancing sleep habits, and using medications to alleviate pain and other symptoms. While medications can prove valuable in managing migraines, they present certain challenges. The main challenge lies in the fact that not all people exhibit a positive response to these medications. Additionally, few individuals may encounter adverse effects from the medications, rendering the treatment unmanageable. Excessive usage of these medications for acute relief can result in medication-overuse headache, a condition where headaches become more frequent and more intense. An additional obstacle lies in the restricted availability of medications that prove effective.

A wide array of medications used to address migraines were initially designed for different purposes, such as relieving high blood pressure or alleviating depression. Consequently, their effectiveness in mitigating migraines can be inconsistent. These difficulties have spurred an increasing curiosity in alternative treatments, including acupuncture, which could potentially offer a secure and efficient solution to combat migraines. In contrast to medication, acupuncture is non-pharmacological and does not pose the hazard of side effects or overuse, rendering it an attractive choice for certain individuals.

Scalp acupuncture, which is believed to have been developed in the 1970s, is a technique that entails inserting needles through specific locations on the scalp to address a range of health conditions. While acupuncture itself has a long history in traditional chinese medicine (TCM), scalp acupuncture is a relatively recent innovation. This method is thought to be particularly beneficial for conditions that affect the nervous system, like migraines, stroke, and Parkinson's illness, due to its capacity to stimulate specific regions of the brain and the central nervous system.

Recently, there has been an escalating interest in using scalp acupuncture as a remedy for migraines. This form of acupuncture, which encompasses needling beneath the aponeurotic layer of the scalp, has the potential to alleviate pain by promoting relaxation of the tissues, modulating the central nervous system, enhancing microcirculation, and regulating blood flow. Numerous studies have explored the effectiveness of scalp acupuncture for migraine; however, the outcomes have not been consistent.

While few studies have illustrated a remarkable decrease in the frequency and intensity of headaches, another study found little to no discernible benefit. Additional research is required to gain a comprehensive understanding of the possible advantages and limitations of this therapy in the context of migraines and other nervous system-related conditions.

RATIONALE BEHIND RESEARCH

While medications are commonly used as the primary treatment for migraine, their effectiveness is still uncertain. As a result, alternative therapies like scalp acupuncture have been gaining attention. Nevertheless, the available evidence supporting the effectiveness of scalp acupuncture is limited. Hence, this study was carried out to contribute valuable insights into the effectiveness and safety of scalp acupuncture as a therapeutic option for migraine.

OBJECTIVE

A systematic review and meta-analysis of the studies was conducted that are currently available concerning the effectiveness and safety of scalp acupuncture in the treatment of migraines. The objective was to consolidate all the accessible data in order to deliver a conclusive evaluation of how well this therapy works for migraines and to pinpoint any potential factors that could influence its effectiveness.

Literature search

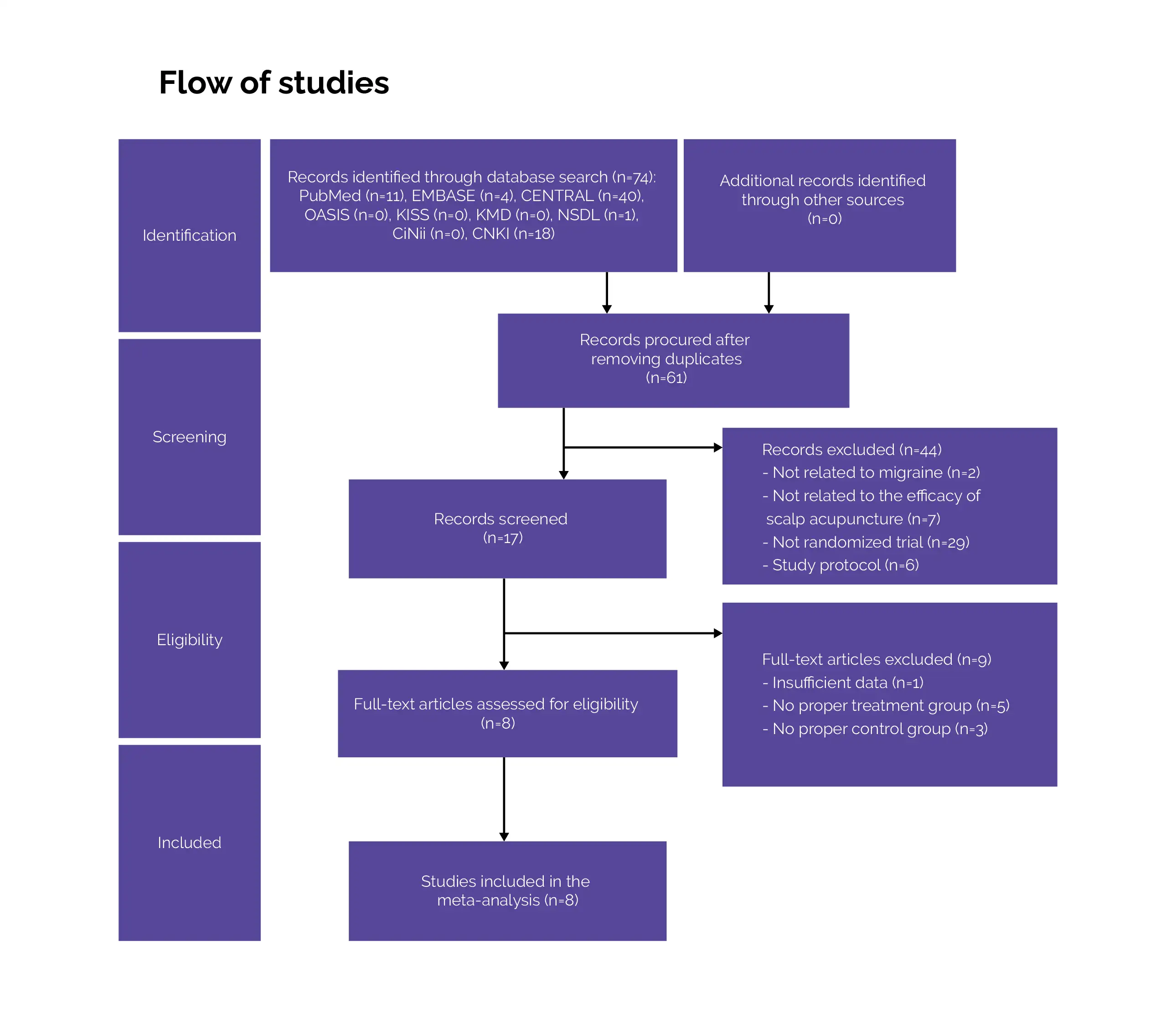

Searches were carried out in several databases, including China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Citation Information by NII, National Science Digital Library (NSDL), PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Korean Medical Database, Oriental Medicine Advanced Searching Integrated System, Korean Studies Information Service System, and EMBASE.

The search encompassed the period from the inception of these databases up to September 2022, with no language limitations, in order to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Inclusion criteria

(a) Study types

RCTs that specifically addressed the application of scalp acupuncture to relieve migraine were considered for inclusion.

(b) Participants

Participants who had received a migraine diagnosis according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders and had been treated with scalp acupuncture, without any limitations based on gender, race, or age were eligible for inclusion.

(c) Interventions

Those studies were included that primarily focused on scalp acupuncture as the main intervention, along with other treatments like thrombosis therapy, body acupuncture, and electrical stimulation as supplementary therapies. The inclusion criteria were based on the definition of scalp acupuncture, which encompasses the treatment of specific zones on the scalp linked with various body functions and broader regions of the body.

This technique involves inserting needles into a thin layer of loose tissue just beneath the surface of the scalp at a low angle of approximately 15–30 degrees. The insertion depth is typically about 1 cm, followed by rapid stimulation through various methods like pulling, thrusting, twirling, and electro-stimulation. In this analysis, two forms of scalp acupuncture were taken into account: Yamamoto's new scalp acupuncture (YNSA) and Qinshi scalp acupuncture.

(d) Comparison

Those studies were included in which the control group included patients who received alternative treatments, like medications, physical therapy, or sham therapy, as well as those who did not receive any form of therapy.

Exclusion criteria

RCTs that did not adhere to the principles of scalp acupuncture theory, such as those that did not involve needling or did not target specific points according to the scalp acupuncture lines, were eliminated.

Studies that incorporated scalp acupuncture as a part of the control group and those with unclear descriptions of their control groups were not considered for inclusion.

Study selection and Data extraction

Following the elimination of irrelevant studies through title and abstract reviews, two independent reviewers thoroughly assessed the full texts of each included article. These reviewers systematically extracted, analyzed, and organized data pertaining to the study design, participants, interventions administered, control group treatments, outcomes, and other relevant factors.

The results of the search were subsequently cross-verified. In instances where data were found to be insufficient, efforts were made to reach out to the authors for additional information. If such data could not be procured, the study was expelled from the investigation.

Data and Statistical Analysis

Two reviewers collected and analyzed the data independently. For assessment of the robustness of the results, a sensitivity analysis was executed. An iterative meta-analysis was done by systematically eradicating one study at a time. Relative risk (RR) was employed for analyzing dichotomous outcome data to determine treatment effects. When dealing with continuous outcomes, standard mean differences (SMD) were utilized. Point estimates, along with their 95% confidence intervals (CI), were used to represent both dichotomous and continuous data.

To ensure the reliability of the meta-analysis findings, the robustness of the findings was investigated using two critical metrics: the fragility index (FI) and fragility quotient (FQ) for statistically significant outcomes. The FI was calculated using an online calculator available at http://clinicalepidemio.fr/frgility_ma/. The results were categorized as highly fragile if their FI was less than or equal to 1 or if the FQ was less than or equal to 0.01.

RevMan software was utilized to perform all the meta-analyses. A quantitative synthesis was carried out with the aid of a standard effects model when there was no statistical heterogeneity. The effect sizes were presented with 95% CIs. The findings were deemed statistically significant if P < 0.05. Q and I² tests were employed to assess heterogeneity presence. A fixed effects model was chosen when P > 0.1 and I² was less than 50%, indicating the absence of significant heterogeneity.

In cases where P < 0.1 and I² exceeded 50%, indicating substantial heterogeneity, a random-effects model was employed. Owing to the restricted number of studies in each comparison, a subgroup analysis was not conducted.

Risk of Bias and Quality assessment

For assessing the risk of bias, the RoB 2.0 tool was employed. A meta-analysis was executed utilizing RevMan software (Version 5.4). Determination of the certainty of the evidence was done with the aid of the GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool. Various factors were taken into account to assess the confidence in the evidence, including imprecision, indirectness, inconsistency, risk of bias, and study design.

The level of confidence in the evidence was graded as high, moderate, low, or very low. Study bias was categorized into one of three levels: 'some concerns,' 'low risk,' or 'high risk,' based on the following criteria: random sequence generation, deviations from intended interventions, missing or incomplete outcome data, measurement of the outcome, selection of the reported results, and overall bias.

Study outcomes

1. Total effective rate: This metric indicates the percentage of patients who achieve a favorable outcome following treatment. It encompasses categories like 'complete cure,' 'good effect,' and 'effective treatment,' while excluding those with no response. This outcome measure was chosen because it has been widely utilized in Chinese RCTs to assess efficacy.

2. Pain-associated outcomes: To assess the treatment's impact, the frequency and duration of pain was examined. Assessment of pain intensity was done using tools such as the visual analogue scale (VAS) and pain rating index (PRI).

3. Questionnaires related to migraine: The migraine therapy assessment questionnaire (MTAQ) and migraine disability assessment questionnaire (MIDAS) are commonly employed for migraine evaluation. The MIDAS questionnaire helps gauge how headaches affect an individual's life, assess the pain and disability levels, and identify the most effective treatment options. The MTAQ is used to evaluate the degree of migraine management both before and after the intervention.

It consists of nine questions that encompass five key areas: symptom control, attack frequency, barriers related to knowledge and behavior, economic implications, and the overall satisfaction of the patient with migraine treatment. These questionnaires were utilized to assess the treatment's impact.

4. Body changes: Researchers have sought to comprehend the treatment's impact by examining hemodynamic indices in the posterior, anterior, and middle cerebral arteries. Furthermore, several studies have employed calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), endothelin-1 (ET-1), and CGRP and 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT).

5-HT are neurotransmitters and vasodilators, respectively, affecting the dilation and relaxation of cerebral blood vessels. ET-1 is a naturally occurring signaling molecule released from blood vessels. These compounds have been associated with the emergence of migraine headaches and were therefore considered in the assessment.

5. Headache index: This index comprises parameters such as pain intensity (VAS), the frequency of attacks, duration, and related symptoms. This has been a recurring characteristic in the Chinese studies. The inclusion of this index is valuable as it encompasses essential measurements pertaining to headaches.

Outcomes

Study and participant characteristics:

Study quality:

Effect of intervention on the outcome:

Two trials employed medications containing flunarizine hydrochloride, while Yuan et al. used naproxen, both of which are widely used to alleviate migraines. This choice made them the most suitable options for evaluating scalp acupuncture efficiency. The acupuncture points utilized for ordinary acupuncture (other acupuncture) consisted of GV20, GB20, EX-HN5, LI4, and LR3, with the majority of them located on the scalp. Additionally, other acupuncture points effective for treating headaches were also incorporated.

Consequently, it is crucial to distinguish between the effectiveness of scalp acupuncture and that of other ordinary acupuncture techniques. Two of the trials incorporated in the review conducted follow-up assessments on patients after they completed their treatments. In the study by Yuan et al., patients were followed up at 1, 2, and 3 months post-treatment to examine the therapeutic effects. The assessments included the use of the VAS and TCM syndrome scores in the first month, VAS scores and TCM syndrome evaluation in the second month, and VAS scores, TCM syndrome evaluation, and factors such as sex and education level in the third month, all of which were analyzed in relation to the treatment outcomes.

The study found that both gender and education level can influence the effectiveness of the treatment, with education potentially boosting the treatment's effectiveness through an improved understanding of the therapy and the patient's living environment. Rezvani and colleagues conducted patient follow-up assessments at 2 weeks, 2 months, and 3 months, comparing the effectiveness of YNSA and ordinary acupuncture. Their findings revealed that the efficacy of scalp acupuncture and ordinary acupuncture treatments varied over time when considering distinct outcome measures.

These findings from the follow-up studies indicate the necessity for additional research. Moreover, it's vital to discuss the exclusion of certain trials from the meta-analysis because they contain important information that could be beneficial for future research. For instance, the study conducted by Zhang was excluded due to the presence of 3 experimental groups without a control group. In this review, a comparison was done based on the retention time of scalp acupuncture, and all findings consistently indicated that acupuncture sessions lasting 20 and 40 minutes were highly efficacious than those lasting 10 minutes, with no notable difference in effectiveness between the 20 and 40-minute durations.

Consequently, it is recommended that scalp acupuncture be administered for a minimum of 20 minutes to achieve the desired effectiveness. The study by NG was eliminated from the review because it did not primarily focus on scalp acupuncture. In this trial, the effects of cranial sacral therapy were affirmed by comparing a group that received both scalp acupuncture and cranial sacral therapy (experimental group) with a group that received only scalp acupuncture (control group). The outcomes revealed no profound distinctions between the two groups, except for a variation in the duration of pain experienced.

Hence, it was concluded that there was no vital change in the management of migraine headaches, regardless of whether craniosacral therapy was included or excluded. While this study has offered promising insights and made significant contributions, it's crucial to acknowledge and address its limitations to gain a precise vision of its scope and implications. When summarizing the risk of bias and the quality of evidence in the studies incorporated in this review, it became evident that the overall quality was low. Many of the studies had unclear bias, and the quality of evidence for all the studies included was assessed as either 'low' or 'very low'.

Furthermore, numerous meta-analyses revealed high levels of heterogeneity. For instance, in one trial that examined the frequency of headaches between the scalp acupuncture and ordinary acupuncture groups, the results exhibited significant heterogeneity, mainly due to the minimal difference in the effect size between the two groups. Likewise, in a study investigating the headache index between the scalp acupuncture and medication groups, it was observed that only a small number of people displayed a more substantial effect size, resulting in a high level of heterogeneity in the results.

In this systematic review, most of the RCTs that were included used scalp acupuncture alongside supplementary treatments, such as electrical stimulation, thrombosis therapy, and body acupuncture, as part of their intervention. Therefore, interpreting the outcomes proved challenging as the control groups did not undergo similar supplementary interventions. For addressing this concern, additional high-quality RCTs that specifically employ scalp acupuncture as a standalone treatment are needed. Given the significance of pain management in relieving migraines, it would have been beneficial to include a single standardized pain measurement index in the assessment.

Only 4 trials reported results using pain indices like the VAS and the PRI. Hence, it is crucial for future studies to incorporate a single official pain measurement indicator to ensure reliable and consistent results. Conversely, a limited number of trials utilized questionnaires such as the Short Form-36 (SF-36), the MIDAS, and the MTAQ, which are commonly employed tools for assessing migraines. The diversity in pain measurement indices used across different studies hindered direct comparisons. Consequently, the inclusion of a reliable and standardized test would have offered more definitive and conclusive findings regarding scalp acupuncture efficiency.

Xie and colleagues introduced a 'headache index' as an outcome measure; however, its definition varies slightly from the one detailed earlier, which encompasses variables such as VAS, attack times, duration, and accompanying symptoms. The Xie et al. study results were consequently omitted from this analysis due to the disparity in outcome measures. It would be advantageous to establish a consistent and standardized pain index to streamline research findings and enhance communication within clinical and research domains. Rezvani and co-authors addressed several related concerns in their discussion.

This systematic review marked the initial exploration of the combined effects of scalp acupuncture in the context of migraine treatment. In contrast to a recent review focused on acupuncture for migraine management, this review not only highlighted the significance of scalp needling but also encompassed specific approaches, including those introduced by Qinshi and Yamamoto.

Furthermore, it affirmed the potential of this therapy as a viable substitute for conventional therapies. Additionally, none of the studies included reported any adverse events related to scalp acupuncture. Consequently, the safety of this treatment approach remains unconfirmed. Moving forward, it is imperative to conduct numerous rigorously designed, large-scale, multicenter, randomized controlled studies to ascertain both its safety and efficiency. The results of this study could offer important information for medical care providers and those dealing with migraines. This could aid clinicians in making informed treatment choices and ultimately lead to better outcomes for patients.

Scalp acupuncture appears to be more effective than both ordinary acupuncture and medication in the treatment of migraines. However, the safety of scalp acupuncture is still not well-established. Furthermore, due to the limited quality of available evidence, it is imperative to carry out more rigorous RCTs with larger sample sizes conducted at multiple centers to gain a deeper understanding of this therapeutic approach.

Complementary Therapies in Medicine

Effectiveness and safety of scalp acupuncture for treating migraine: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Che-Yeon Kim et al.

Comments (0)